Living with God: a Personal Reflection on Monasticism

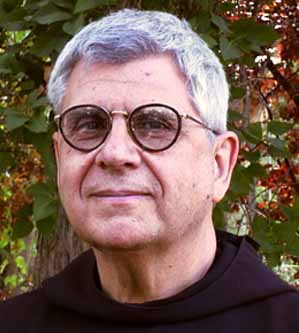

Fr. Aelred Niespolo, O.S.B.

FR. AELRED has completed his Masters in Theology at Oxford University; he was ordained to the priesthood during the summer of 2005.

FR. AELRED has completed his Masters in Theology at Oxford University; he was ordained to the priesthood during the summer of 2005.

Links to Fr. Aelred’s Poetry and Homilies:

St. Aelred of Rievaulx, A Feastday Homily

Fr. Aelred shared something of his story during a retreat conference which was subsequently published.We reprint it here with permission:

LIVING WITH GOD

A PERSONAL REFLECTION ON MONASTICISM

Originally presented during a retreat at St. Andrew’s Abbey

I HAVE not found it easy living with God.

My own life’s course, my journey, has been characterized by this uneasiness.

During this journey I have tried to learn what is truly important; not only for myself, but for others. What makes us who we are? What is essential to being human, and Christian?

The discovery of “others”, (that “others” do exist outside the nexus of desires that make me up) provide the necessary and dynamic tension leading to genuine interiority, and ever-deepening, active compassion.

It is the work of a lifetime, stopped and started over and over again, with its massive and often discouraging failures, and the slow coming to terms with our own mortality. I strongly feel that monastic values and practices help me tremendously in this search. I also know that the reason people are called to this life apart is because they cannot really, honestly, search outside of it. I am here because I need to be, not only because I want to be. I guess that is what a vocation is: being where I need to be, in order to find out who I am. And it is only in finding out whom I am that I can, with integrity, and honesty, search for God. It is really only in finding this true self and God that I can genuinely help others in their own search.

If you will forgive the narcissism, I’d like to share a little of my own life.

I was a Jesuit for 10 years, during that time taught philosophy and literature at Loyola Marymount, where I met three young monks studying at Loyola: Brothers Thomas, Gregory and Francis. (Bro Thomas is now Fr. Romuald, a Camaldolese hermit, you probably know Father Gregory, and of course you know Abbot Francis.) I was dissatisfied with my life as a Jesuit. I felt there was too much entitlement, or at least I experienced it as such. The commitment of those three young monks impressed me greatly, and intensified the longing I had for a more simple life. After two years at Loyola I came to Saint Andrew’s and spent ten months assessing my life as a religious and the possibility of a monastic vocation. At the end of that time I decided to return to the Society and taught for a year in San Francisco. I did not, during all those years, really face up to what was going on inside of me. I was unhappy and distressed. So I took an official leave from the Jesuits and decided to move to Europe, something I had always wanted, yearned, to do. I wanted to experience all the aspects of life I had not allowed myself to experience. I went to Europe, knowing virtually no one, having little money, no clear idea of what I was getting into, or of how I was to survive. I went to live in Germany without knowing German, stayed there six months, supporting myself by teaching at U.S. Army bases, then moved to England. A friend of mine from college had studied at Oxford, and still lived there. I decided to join him. What I was not aware of was that I would live in a squat in Jericho, an area of Oxford. It was quite an experience for a formerly coddled young Jesuit. Now for those of you who do not know a squat is a building or home, whose owner is unknown, and has been left to fall into ruin. By city law, it is open to whoever wants to live in it. For the two years in Oxford, with occasional work, some studies, I lived in a run down Victorian squat: no hot water, outdoor loo, virtually no electricity, peeling walls, creaking floors etc. And yet I had never been happier. I made close friends who seemed to accept me for what I felt I was, not for what I pretended to be.

During my initial teaching years and traveling years I read three books that influenced my thinking and focused my desire: none of them were religious. The Dispossessed by Ursula K. LeGuin, Ringolevio by Emmett Grogan and The Making of A Counter Culture by Theodore Roszak. They spoke to me of political disestablishment, shared goods and community, and the visionary idea of remaking the world. Three ideas that motivated me.

On returning from Europe, I knew that I had to live my life in a way that was part of the solution, not part of the problem, as the slogan from that time had it. I was a good child of the late 60s and 70s.

I wanted to ease the deep isolation and loneliness I felt in myself. I wanted to belong to a place that I valued, and be part of an accepting community. I wanted to try and help create something truly new: as William Blake wrote, cleanse the doors of perception, and see everything as it is – infinite. All very noble ideas. And in some ways very naïve. But at the root of it: I did not want to be alone. I wanted to be chosen for something.

I visited Saint Andrews again, and stayed for four years. During this time I was finally able to figure out what my needs truly were, and the ignorance I had about who I was. I kept defining myself far too externally. I had so much confused desire, and frankly, not enough real direction to help sort it all out, and be happy at the monastery. With a profound regret and some relief I left the only place I had ever felt accepted by, and was also able to call home.

I began two decades of searching. It’s far too complicated to go into, but I landed in New York, back to Europe, to Seattle, to Chicago. I worked at office work, (always at places that gave me an external identity,) text editing, stage and film acting, bar tending, waitering, catering. To find work that did not compromise my ideal, or hurt or use others. Always looking in those situations for something I could belong to, wanting to turn every job situation into a family situation. To bottom line it: I wanted to find love. And, at the same time I was trying to live, all around me friends were dying of AIDS. I could not help being (and I did not want to, let me tell you,) aware that something prevented me from living. A key ingredient was missing.

In moving from place to place, job to job, relationship to relationship, the same gnawing existed. I had all the right instincts, but could not get out of myself. (This is where the “other” comes in.)

I realized that the discovery of the self is intimately tied up with the search for God. I can’t truly find God until I attempt to integrate my own personality in truth, and accept who I really am, not who I want to be, or who I think I am, or who I think I ought to be. We all create an ego, a persona in order to survive, and we must see how false this persona is. And it is only with this initial recognition that we can begin to truly find God. We have to lose ourselves before we find ourselves. This is part of conversatio.That is the primary way we let God into our lives.

(You may ask, if so, if ego is the problem, why not be a Buddhist? It is after all, a vital tradition that leads to deep compassion? And also seems to have far fewer rules. The answer to this lies in the incarnate Christ found in others.)

I realized a few things about what I wanted and where I might be able to find it.

The monastery is a community, a stable family, whose goal is to help its members find God, and follow the consequences of that found and loved God. I more than need to recognize Christ, I must welcome Him. We challenge the false identity we create in order to search for the real. We use lectio (the word Incarnated in us), silence (listening to the word, our “otic” stance), community (dealing with the “other”), stability (focus) and obedience (redefining the ego, selflessness) to do this. Every one of us has a self-protective, constantly mutating self. We are all protean creatures, ever changing in order to always protect our self-image. Dealing with that false self is what spirituality and asceticism are all about.

The hallmark of a true, Benedictine spiritual life is attempting to always live in the Truth: within a cenobitic community that is open to the world, as it is lived. Not only is the monk called to live in truth, but the Benedictine monk must be a sign of Truth to others who live “in the world,” and help them to live their own truth, the truth of their own story. (Ultimately, I guess, it is God Who will tell us our story, and reveal to us our true name.)

The truer I am to myself, the more I see and find Christ in others. The more I minister to them, and am ministered to, by them, the more I help others find out who they are and find the “one thing necessary”. The bottom line of it all is the Lucan Great Commandment regarding God and neighbor. We must help each other find the proper form of service we are called to; and help each other to be faithful to what we are called to be.

Part of being a monk is recognizing the dynamics of victimization that deeply permeate our society, (and in fact has always permeated man’s conscious history). This is one of the things you can help us concretely comprehend. Perhaps that is Original Sin — this need to define oneself by victimizing another. Christ is the blameless victim who forgave, died and redeemed. We need to be truthful to that profound reality. For a Christian this always involves the mystery of the Cross in our lives.

Very often monks can be unaware of what it takes to live in the world. I am, to be honest, often shocked by the naiveté of my brothers who did not have the life experiences I have had: to pay rent, health insurance, the anxiety of not knowing where the next meal comes from, or not having appropriate shelter, or to be totally isolated from others in society.

The monastery must not be co-opted by the values of the world or else it loses its truth.We have to be called to account when we become worldly and comfortable and unfeeling and self-centered. We have to guard against treating the people who work for us unfairly, by not providing adequate wages and benefits.

We know the way the world deals with those things that shake it up:

Send Us a

Prayer Request

Every day the monks include the petitions they receive when they pray the Liturgy of the Hours. Let us know how we can pray for you!